Back To Home - The Story - Timeline - Gallery - PC Week Excerpts - My Tutorial - Their Tutorial - Their Marketing Copy - GSX and GSS-CGI - Archive.org uploads

The History

Imagine, for a moment, that it's 1981. You've just seen the announcement of the IBM Personal Computer, and you know that IBM's market dominance is sure to help this new system drive the Apples and Tandys of the world back into irrelevance. You also have seen the Xerox mouse demos, and correctly recognize that graphical interfaces with a pointing device are the future, not just textual command lines. You and a few friends devise a plan: you'll create a piece of software to allow regular office computer users to do the page layout and publishing work that right now is the domain of extremely expensive and specialized printing houses, and you'll do it in a graphical way to make it easy to use. The Mac and even the Lisa are still years out; this is a largely unprecedented idea. It's a million dollar plan, possibly a billion dollar one, and you have plenty of time to define yourself as a market maker.

Then, you proceed to completely squander that brilliant plan by chasing a string of dead-end technologies, being relevant for a very brief period and vanishing into history immediately after, almost entirely forgotten by the world and survived by only a single entry in the Computer History Museum. That is, until some idiot bought a set of neat-looking floppies on eBay that turned out to be a surprisingly comprehensive archive of your company and possibly even the last copy of your software in the world.

If it's not clear, it's me, I am the idiot in this story.

This is the tale of Studio Software Corporation and their ill-fated entry into the desktop publishing market, before that class of software had that name and largely before it even existed. I picked up this set of disks because they had software labels for something I didn't recognize and couldn't easily find and I figured it'd be fun to archive it as I'd been gaining experience with the GreaseWeazle and wanted an excuse to do more with it. Instead I wound up down a rabbit hole that took me most of the way to the Earth's molten core, as the set turned out to contain copies of the finished software, sure, but also random development artifacts, tech demos, internal tools, backups of one employee's PCs, and most excitingly, the source code. In effect, I now own Studio Software Corporation. Let me show you what I found.

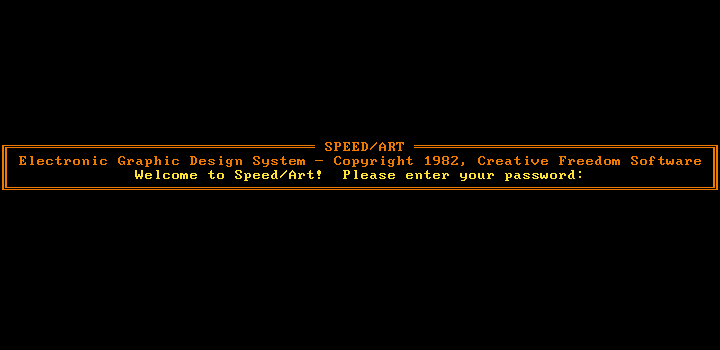

Technically, our story actually starts even earlier in May of 1978, with the founding of a company called California Coastal Service in Santa Ana, California. I have absolutely no idea what CCS was founded to do, probably computer or general electronics repair, but it was under this company that work began on Speed/Art in 1981-82 (the exact date isn't known). Speed/Art was a BASIC program that was designed to do page layout, though it could only handle one page at a time and the interface was fairly simplistic and sluggish. It was, however, graphical, and while it did not immediately have support for pointer input devices the source had placeholders for them, so it was clearly a planned feature. With work well underway on Speed/Art, CCS renamed itself to Creative Freedom Software in July of 1982 and moved to Costa Mesa, California, with several of the founders each contributing capital and labor to fund this new company.

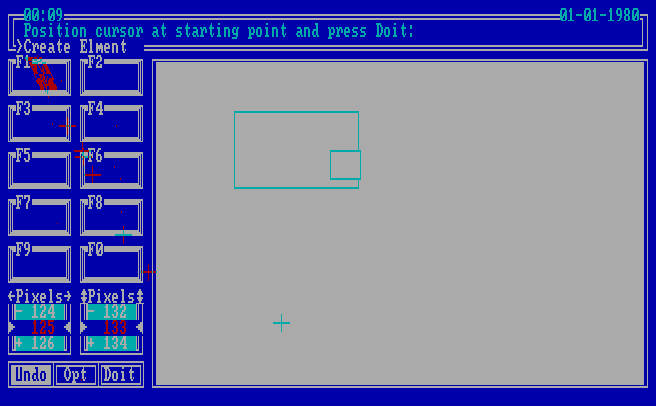

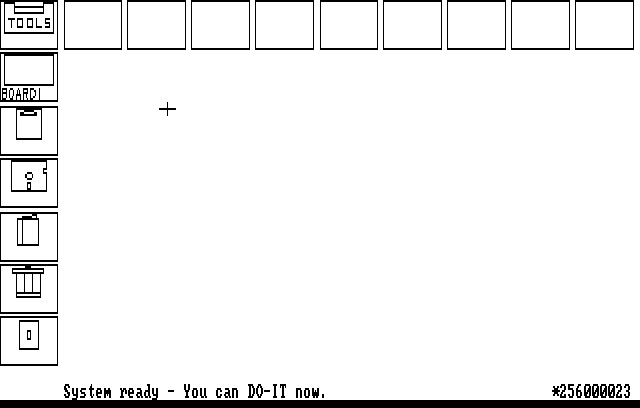

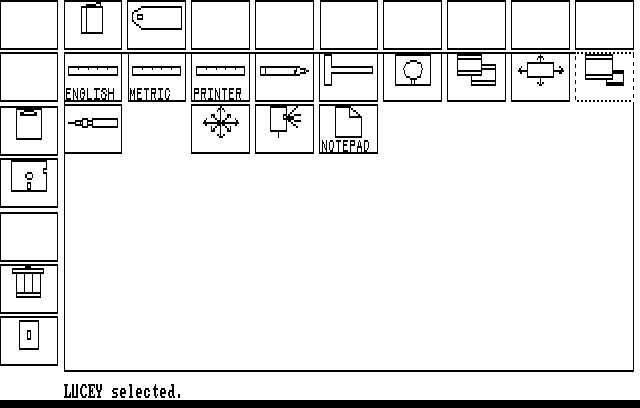

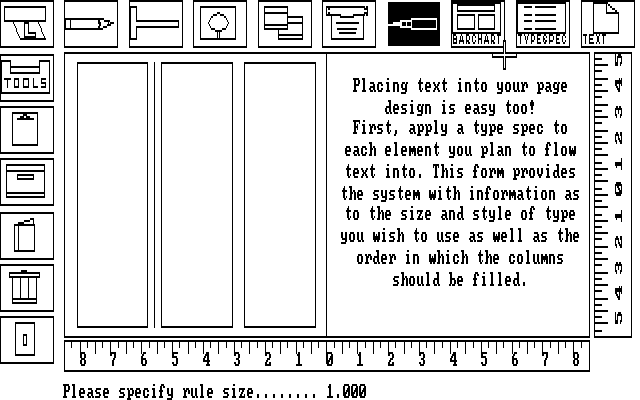

Various versions of the BASIC source of Speed/Art survived, but almost none work as-is and at least some are incomplete. There is one surviving release disk with a "Speed/Art Demo" label dated from February 1982, though the actual files on it are from February of 1983. This version works, and even has several advanced features compared to the various development backups--namely, it can use a gamepad for cursor input, and it has more advanced graphics that require a Platronics Colorplus card. The demo is very basic, but it was in fact a graphical interface, on the PC, in 1983, using the game port for pointer input. A set of function buttons adorned the left side of the screen for functions like "Create" and "Fill" that you could press to access a submenu with a second set of buttons like "Element and "Text", with what would today be called a status bar at the top, pixel coordinate displays for the cursor, and three extra buttons labeled "Undo", "Opt", and "Doit". If I had seen this in February of 1982, as the disk label states, my jaw would have been on the floor. Even by 1983 this would still have been pretty wild on the PC. Even VisiCorp's VisiOn would not be released until the end of 1983.

I do not know if Speed/Art was ever sold as a commercial product--I have been unable to track down primary sources from that era. Based on the surviving copies, it seems likely this was at least the plan, as they have a decent feature set implemented for a proof of concept. Oddly, very little of Speed/Art was implemented in the one surviving compiled demo. Perhaps it was genuinely a deliberately-incomplete demo, as the source versions implement more of these functions; this would lend credence to at least the intent of selling Speed/Art. But within the demo, "Fill Text" prints a placeholder text to the screen about how the average businessperson doesn't know what computers can do, and "Create Element" lets you draw elements (hollow rectangles to contain content) on the screen, a function and term that would persist.

The Speed/Art name, however, would not. Somewhere in 1983 Creative Freedom Software began using the "DO-IT" brand instead, derived from what was surely a placeholder text. By buying this software, you, too, could DO-IT. It is not known if Speed/Art was renamed or if this was a new program entirely, but from the lack of evidence otherwise my assumption is it was what used to be Speed/Art. Almost nothing has survived from this era of SSC to know for sure, despite the otherwise rather extensive archive I acquired. All I have are some files with a copyright notice of "DO-IT 1.03c, 1983", but the actual DO-IT 1.03 would be years away still and to the best of my knowledge there never was a "C" or even "B" suffix used for that software. Oddly, every file with this notice says 1.03c, no other version. Unless somebody else is even luckier finding archives of this software than I am we can only speculate as to the details here. It is also not clear whether the correct branding is the all-caps "DO-IT" or the title-case "Do-It"; Studio Software seemed to use both at various times, but the all-caps version seems to be more common and is what I will be using to refer to this software.

Nor did Creative Freedom Software's own name survive; in October of 1983, barely a year after CFS was founded, they renamed themselves to Studio Software Corporation and moved to Irvine, California. What is known is that in December of 1983 Studio Software began work on a new program with the DO-IT brand, this time written in Pascal. Development quickly ran into a serious technical limitation: the PC just wasn't up to the memory requirements of what DO-IT wanted to do. Even with a PC maxed out at 640KB, the program and its data would not fit. So, SSC made use of Digital Research's Pascal compiler's capability to have parts of the program in what it called "overlays", which would be dynamically loaded and unloaded as needed. This, combined with using both floppy drives, got DO-IT to fit in the space available. The overlay files could then be stored in a RAM disk made from expanded memory. A pretty clever solution, given the tools available at the time.

But what about the operating system? Under Creative Freedom Software, the developers were using all three original PC operating systems: PC-DOS, CP/M-86, and UCSD p-System. By 1983, they had abandoned p-System, settling on CP/M-86 as the expected winner. After all, CP/M was everywhere, so CP/M-86 was sure to win out. UCSD p-System vanished entirely from SSC after 1982, though PC DOS hung around in the background, just not used for commercial releases.

Those of you reading this from anywhere after 1983 know that CP/M-86 did not win. Even by 1983 its marketshare was a niche at best; by the time DO-IT launched in 1985 it was a footnote. I don't have a clear reasoning for why this choice was made. There's always the possibility it was just somebody's favorite, of course, but one interesting idea I've seen suggested was that since DO-IT shipped with a booter floppy which necessitated an operating system to boot into, it may have been cheaper on the licensing to distribute CP-M/86 than PC DOS. However, booting its own copy of CP/M-86 did not absolve it of issues with DOS compatibility. After all, you were expected to import word processing files, which were hopefully on a disk that CP/M-86 could read. Converter software existed, but would have been an additional complication.

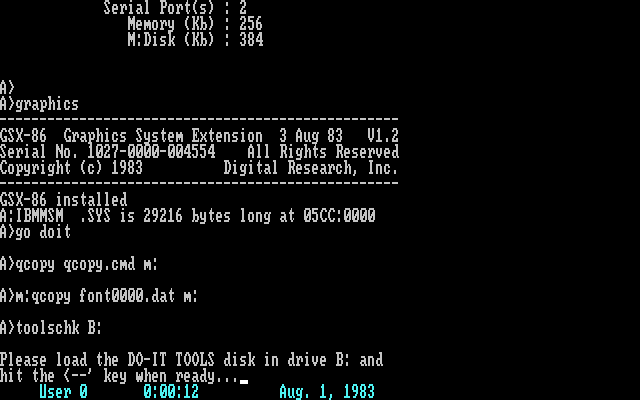

The next question was how to render the software, as windowing operating systems were still effectively in the prototype stage as a whole, with only Apple having a working (if primitive) example and the rest of the world scrambling to catch up. By now, SSC had access to Digital Research's implementation of the Graphical Kernel Standard (GKS), named the Graphical System eXtension (GSX). GSX would handle graphical output, as well as pointing device input, and printer and plotter output. This would allow them to handle MDA/Hercules and CGA graphics both without needing to write their own video drivers. GSX was sure to be a huge hit on the PC, just like CP/M-86.

Second verse, same as the first. There's decent documentation about GSX-on-CP/M-86, but next to nothing for GSX-on-DOS. Pretty much the only information I can find about GSX-on-DOS is "it existed". GSX also brought us GEM on the PC, an also-ran windowing environment on the PC that didn't accomplish much of note there (it also give us GEM on the ST, which actually had some degree of success, but there is sadly nothing about the ST in this tale). GEM, however, wasn't the only framework built as a successor to GSX... but more on that later. While I think GKS/GSX was defensible at the time the choice was made, this quickly proved to be more and more of an issue as time went on and full windowing operating systems began gaining market share.

Finally, there was a question of input devices. Mouse Systems had brought their PC-compatible mouse to market in late 1982, followed by the original Microsoft mouse in May 1983, but there was no standardization yet, and the PC's game port was not really up to the task of handling a pointer device. Perhaps nor did it seem very professional to instruct businesses to buy their employees joysticks to do typesetting and page layout. As such, SSC made the decision that DO-IT would support the SummaMouse from SummaGraphics, which is something I'd never even heard of before this but seems to be a pretty close relative of the original Mouse Systems mouse, for which support was also added in short order. Given the mouse situation on the PC remained a mess until the PS/2 mouse started becoming widespread I can't really fault them for picking an uncommon mouse.

With these technical decisions made, Studio Software began releasing betas of DO-IT in 1984, running under CP/M-86. I have no way of knowing how widely distributed these were, but they appear to have shipped at least enough to collect some feedback. Unfortunately the one beta I have doesn't actually work, but it does have one fascinating (to me) artifact of referring to enter as the "<--' key".

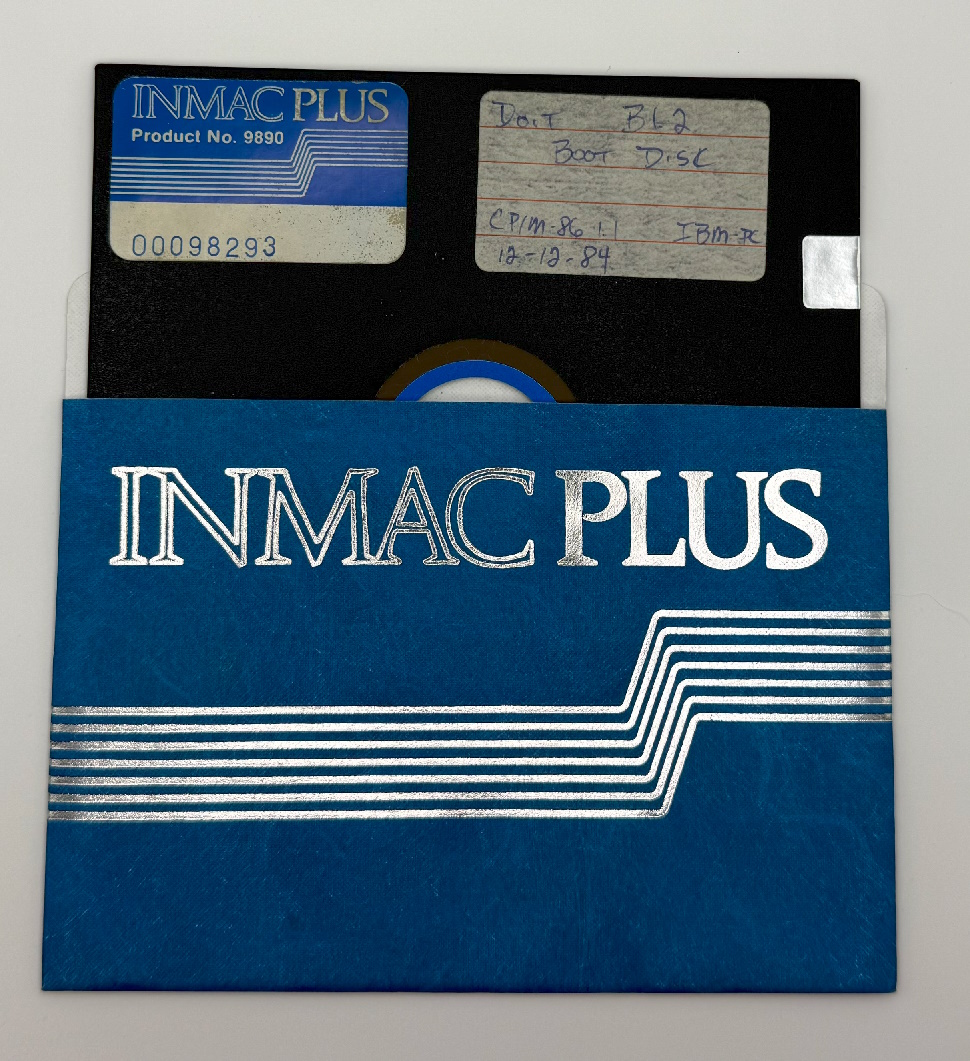

Also, as an aside: look at these very fancy disks SSC was using. If it's not obvious, that's metallic trim on the sleeve.

During this period, Studio Software was purchased by a new entity that assumed the name Studio Software Corporation under a new company president, with the original corporate entity renaming itself to "Old Studio Software Corporation" in advance of this acquisition. Oddly, the renaming and the founding of new-SSC occured in May of 1984, but the merger didn't complete until October. The merger was then followed by the founding of a wholely owned subsidiary named Studio Software Development, Inc., in November of 1984, by the president of the original California Coastal Service. I am not nearly well versed enough in corporate law to offer any explanation as to what any of this was for. I assume this either obscured debt somehow or reshuffled who owned the company, probably to keep the regular employees from getting to make any money from investments in SSC.

SSC made steady if slow progress towards a commercial release. DO-IT 1.0 launched somewhere in early 1985 at an eye-watering price of $2495; sadly I have nothing at all versioned 1.00, but based on other dates and source code change history I believe it would have been February 1985. It was by this time not the first desktop publishing software on the PC, nor the first graphical environment. But it was complete, it was capable, and it was met by collective indifference. The Macintosh had fully enraptured the public by this point, and SSC's technically impressive but visually crude graphics were no longer revolutionary. Nonetheless, SSC kept at it, releasing 1.01 in April of 1985, still for the ever-dwindling marketshare of CP/M-86. But by 1985 it was finally clear even to SSC that CP/M-86 was not going to win the PC market, and that this was increasingly a liability to them rather than the advantage they had hoped for.

Thankfully, Studio Software hadn't totally abandoned DOS in the meantime. Speed/Art itself had been a DOS program, and there were a few development artifacts on disks in DOS format even though the majority from this time period were CP/M-86. Most notably there was an internal tool running on PC DOS simply called DRAW, which as far as I can determine was used to create and edit font glyphs. DRAW does not appear to have ever had a commercial release, likely being used solely internally. Still, they clearly had enough familiarity to begin to port DO-IT to PC DOS. That was one problem solved.

But CP/M-86 wasn't the only thing SSC was technically behind on by this point. The IBM 5170, the PC AT, had launched in 1984, bringing with it high-density floppy drives. A hard drive was also included in all but the cheapest ATs and was increasingly common even amongst XT clones, and this was followed shortly by EGA graphics. SSC, however, made the decision to eschew this segment of the market and continue to target PCs and XTs as its expected hardware--not only would DO-IT not ship support for EGA graphics, it wouldn't even run on EGA unless you set the EGA card to CGA mode. Still, it was at least obvious that hard drives were here to stay, so version 1.02 launched in June 1985 with a new installer that would copy DO-IT to your hard drive and run it from there, rather than needing you to juggle four floppies at startup like previous builds had. But it still required a boot floppy to run--for the entire existence of Studio Software Corporation, they would not release a single product that would run without a boot floppy, a restriction partially forced upon them by how GSX handled its hardware drivers. Nor would they ever release on HD floppies, though they did use them internally later on. As far as I know they never used a 3.5" floppy at all.

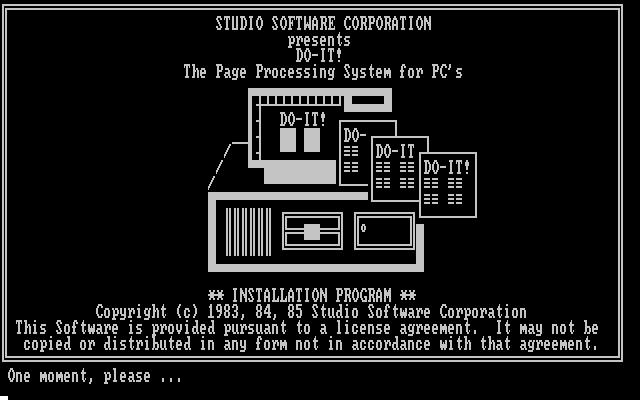

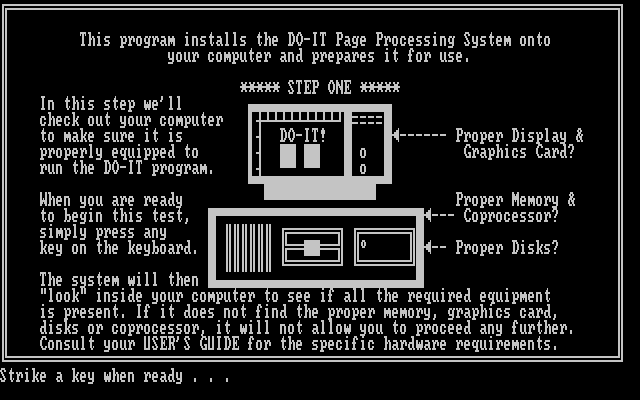

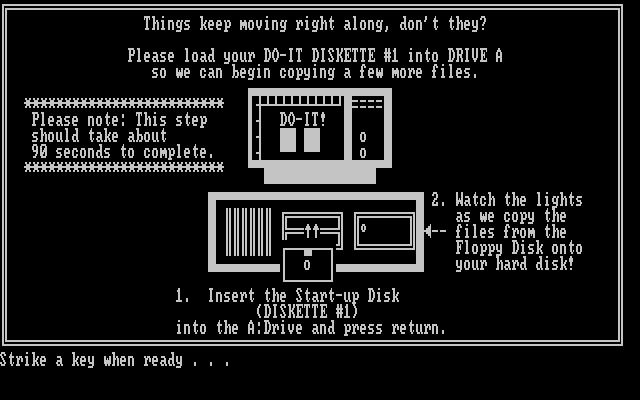

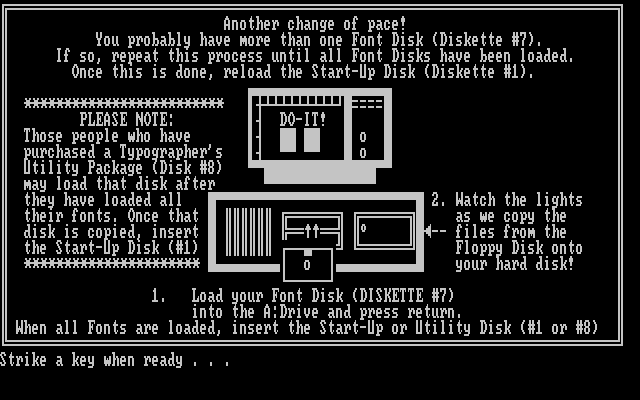

The installer shipped with 1.02 feels like it's quite a bit ahead of its time. It's a wizard-type UI that walks you through installing from the various disks that DO-IT shipped on: Startup (1), Master (2), Tools (3), Storage [sometimes called Data] (4), Proof (5), Output (6), Fonts (7), and Utility (8), and the Install disk itself (0). Disks 6 and 7 could have multiples and disks 6 and 8 were both optional, and the installer could correctly handle the various permutations that a customer might have purchased. All the while it walks the user through the install process with text that's so friendly it's almost cloying. It wouldn't feel out of place today, which is impressive for 1985. Credit to Studio Software for that one.

The landmark 1.02 release was followed by 1.03 in September and 1.04 in December of 1985. The for the time unusually rapid release cycle suggests that DO-IT was not without defects, which likely did not help their market uptake. Following 1.02 work began on something branded "XTRA", which I don't have any information on aside from source code changelog entries referring to that name. I do not know if it was cancelled, or just renamed back to version 1.10, which launched in February of 1986. Alongside this release, Studio Software dropped the price of DO-IT to $1,895 and promised a new lower-end version at only $895; possibly this was "XTRA". These pricing cuts were clearly intended to generate additional marketshare. But all this still wasn't enough: the market remained indifferent to SSC and DO-IT, save a single editorial in PC Week complaining about the name being too generic.

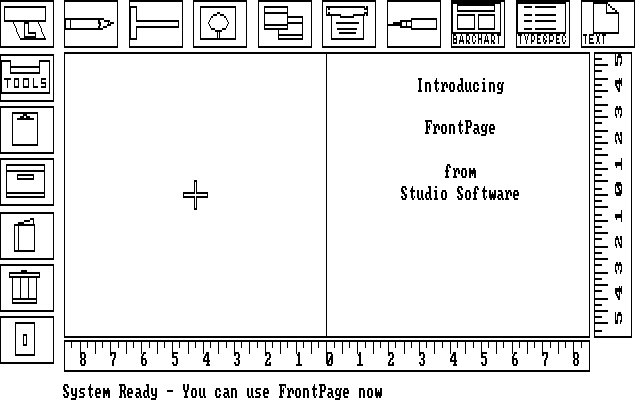

By this point Studio Software was bleeding money very quickly, so without the ability to attract nearly enough customers they opted for the best option they had: a rebranding. DO-IT 2.0, scheduled for later that year, would be released as FrontPage 1.0. It was still DO-IT of course, with the files even still named "DO" internally, and the DO-IT brand would be maintained for their existing customers, at least for a brief period. But SSC believed FrontPage was a stronger brand. They were probably justified in that thought since Microsoft's FrontPage went on to be far more known (even if MS themselves weren't the ones that gave it that name--I wonder if Vermeer ran into SSC's FrontPage while naming it?).

FrontPage 1.0, nee DO-IT 2.0, had some genuinely exciting upgrades. There was a new built-in online help system, uncommon for that era. It had a variety of new tools and upgrades to the existing ones. But most excitingly, it replaced GSX with Graphic Software Systems' implementation of the Computer Graphics Interface (CGI) standard. CGI was another derivative of GKS, and thus a straightforward upgrade path from GSX. With it came support for far more input and output devices, including a variety of mice and, finally, support for EGA graphics. With this came a much more capable installer that let you configure which of several mouse, display, and printer devices you wanted to use. To go with these new upgrades, Studio Software authored a non-interactive demo disk that would walk through a typical use case of the software building a simple document. Finally, they launched an advertising campaign with a much wider reach than before, setting themselves up with new distributors and partners, and ensuring their name was all over PC Week. It was a fantastic effort for this new software.

The rebranding and the upgrades were to be the savior of the company. They had to be; in mid-1986 Studio Software reported a loss of $1.4M on just $940k of revenue for that fiscal year. This level of losses was clearly unsustainable. To try to entice new customers, Studio Software reduced the price of FrontPage even further to just $695, with FrontPage Plus (which included additional output drivers and font management support) priced at $1295. The new EGA support via GSS*\CGI, first seen in the non-interactive demo, would place FrontPage in a very attractive position in the market at that price. But something went wrong. The conversion to GSS*CGI could not be completed in time, and FrontPage 1.0 had to launch with GSX after all, and the revert back to GSX delayed the launch. FrontPage 1.0, still using GSX, was released in August of 1986, lacking the promised EGA support and a month behind schedule. Shortly afterwards in early September, Studio Software formally acquired Studio Software Development Inc., merging back into one company again.

With FrontPage officially for sale, Studio Software announced an IPO, with shares going on sale by mid-October. Through it, the company hoped to raise over four million dollars to cover their mounting debt. Simultaneously, it announced a marketing partnership with AST's Premium Publisher hardware package, where AST would promote FrontPage as one of the software packages compatible with their system. Similar deals were struck with several scanner manufacturers. All the while, Studio Software promised everything to everyone--FrontPage would support IBM's Direct Graphics Interface System, HP's Document Descriptor Language, and seemingly every scanner that someone could ask them about. Most or all of these would never go on to be actually supported.

Compared to DO-IT, FrontPage proved much more interesting to the market, selling more copies in less time. FrontPage 1.1 (DO-IT 2.1) was released in November, finally including the GSS*CGI support promised for 1.0, and compared to the planned 1.0 feature set even added support for the Wyse 700 and the Amdek 1280 1280x800 monitors. But once again, it was not enough. While sales were up, the IPO had to be withdrawn by the end of November for lack of interest, primarily citing the company's debt as the reason for lack of interest. With their hopes of going public dashed, the company knew they were in serious trouble and in early 1987 hired a new chairman and CEO to try to get their situation under control. An additional $1M in venture capital was offered to them, providing a much-needed lifeline as they entered talks to be acquired by ITT.

In the background of FrontPage's release, Studio Software had finally figured out that Digital Research wasn't going to be the winner of the PC market after all and had started to experiment with Microsoft's Pascal compiler and libraries, though this was never used in a commercial release. But while converting from Digital Research's Pascal compiler to Microsoft's tools probably wouldn't have been a huge task, it was increasingly clear to the developers that they had painted themselves into a corner. Windows 1.0 was out, and while Windows wouldn't really take off until 3.0, GEM was also available and that had had enough uptake that their customers were asking about it. SSC's answer to the rapid rise of windowing operating systems was to produce prewritten marketing copy for their resellers telling them that the combination of FrontPage and a windowing system was just too much for computers of the time to handle. Based on the evidence available, it appears that SSC began attempting to correct this by... rewriting DO-IT in C. There are comments in the source code stating "when we switch to C", and in addition to that there are very few changes recorded in the source after FrontPage 1.0 and none at all after October 1986. In fact, one of those last changelog entries states it is for version "3.0" which there is no other reference to. There's no way to know, but it wouldn't be surprising if the planned rewrite was going to be 3.0.

A rewrite, however, was a lot of effort. Was this really the right choice? This was the question the new CEO surely found themselves asking when they joined, especially after the additional venture capital was suddenly withdrawn and the acquisition talks broke off. The answer was apparently "no". Despite a planned FrontPage 1.2, which appears to have never been released, SSC lasted barely two months under its new leadership. It may have just been a review of the company's dire financials, or the effort spent on a rewrite that didn't provide any income, or perhaps it was seeing what it would take to convert FrontPage to a different software architecture to support a windowing system. But whatever it was, the new CEO decided that the company was beyond salvation. Studio Software Corporation closed its doors in March of 1987 with FrontPage having sold just 1500 copies in total. With the pace of the software industry in the 1980s, Studio Software was almost immediately buried by the sands of time as PageMaker and the like quicky grew to dominate the market. SSC tried to offer its IP to others as it shut down, but there were seemingly no buyers. At least until me, 38 years later, but something tells me SSC's owners wanted more than $50 for their IP.

Shortly before Studio Software folded, Apple would release the Macintosh II, which with its color display and "WYSIWYG" capabilities quickly ran away with the burgeoning desktop publish market that Studio Software had been chasing for its entire existence, and turned Apple's lead in that market segment into a runaway success. Desktop publishing arguably kept Apple alive through the 90s as the Wintel world ran away with the computer market in general and ground every other competitor into dust until Steve Jobs returned to give the world the iMac in 1998. The idea of an alternate history where DO-IT takes off enough that desktop publishing never gains a meaningful presence on the Mac leading to Apple dying entirely in the 90s is an interesting one, but one that is certainly pretty far from our own.

And it turns out it wasn't quite true that there were no buyers for Studio Software's IP. Maybe. PC Week reports in May of 1987 that Haba/Arrays, of HabaWrite and /// E-Z Pieces fame, was buying Studio Software's remnants and going to hire some of its employees to try to enter the desktop publishing market and compete against Aldus and similar. However, I can't find any evidence of them ever releasing such a thing, and this may be related to an article from the Washington Apple Pi Journal from almost the same day saying that Haba/Arrays had suddenly disconnected their phone and seemingly disappeared off the face of the planet. It is unlikely we'll ever know what really went down there, but it seems safe to say that even if Haba/Arrays bought Studio Software, then SSC died with them fairly shortly afterward.

This is a fascinating tale of a perfect, brilliant idea that turned into a monument to failure. In my opinion Studio Software were both too early, in that no customer was looking for this yet when they started, and too late, in that they failed to draw attention just for having a GUI with a cursor on the PC before Apple stole the show with the Macintosh. Nor were they helped by constantly choosing losing technologies and only moving on long after the lights were out and everybody else had left the building. From p-System and to CP/M-86, to only getting around to EGA in 1986, targeting PC and XT systems as the expected hardware right until the end even as ATs and clones were running away with the high-end market, and of course backing GSX/GKS into GSS*CGI until the very end. Their company president blamed the entrance of software giants like Xerox and their much larger marketing budgets pushing Studio Software out of the market, but I don't think SSC could have recovered from their technical debt even without the additional competition. DO-IT was a fantastic piece of software in 1984, but the market moved on faster than SSC could keep up.

From marketing copy included as sample text (linked above), FrontPage was competing in the "$500-1000" bracket and the "$1000+" bracket. It describes its competitors as PageMaker in the $500-1000 bracket and SuperPage and Magna in the $1000+ one (I have never heard of either of those two). FrontPage was offered as both "FrontPage" and "FrontPage Plus for Graphic Arts Professionals", but seemingly the only difference was the included printer drivers and whether or not you got the font editor (note: this is not DRAW, this was a different utility meant more to install fonts than draw them). Based on advertisements in PC Week, FrontPage cost $695 and FrontPage Plus for Graphics Arts Professionals cost $1295. FrontPage was apparently introduced as the low-end offering, with DO-IT originally maintaining the $2000 tier until FrontPage Plus took its place. Given that for most of FY86 all that was available was DO-IT at $1895-$2495 until a $895 tier was introduced in January, on that $900k in revenue they barely hit 500 sales in the entirety of that fiscal year. Combined with the published FrontPage sales numbers, the total number of copies sold of either is likely somewhere in the range of 2000-2500. It is not surprising to me that this software went forgotten by history until I stumbled across it--this may genuinely be the last remaining copy in the world.

And while DO-IT is a terrible name for a piece of software, I think it would have worked very well as a name for an overall office suite. If they had managed to... well, a lot of things, they could have had a DO-IT suite that contained Draw-It and Publish-It or whatever. I think that branding would have worked pretty well. Amusingly there was a Publish-It (marketed in the US as Timeworks) that even ran under GEM to make the coincidence even funnier, but to my knowledge there's no connection. I did learn at the tail end of this research that there was an "ItSoftware" bundle that was a variety of things suffixed with "It" like "WritIt" and "CalcIt", so I guess I'm not the only person to have had that thought after all.

So what survived?

What I have of the actual software, in compiled form, is:

Speed/Art demo: this requires a PC or XT and while it has an MDA mode, it looks awful; it really wants Plantronics Colorplus graphics and will not work correctly under regular CGA. It also needs a gamepad. This has two executables, SPEEDART.EXE and SACALIB.EXE; the latter does a joystick calibration at startup and the former does not, making the former functionally unusable unless your computer has the exact performance the code was written to expect and I could not get 86box to hit that (~8mhz 8088 was the closest I could get). Just use SACALIB.EXE if you want to try this.

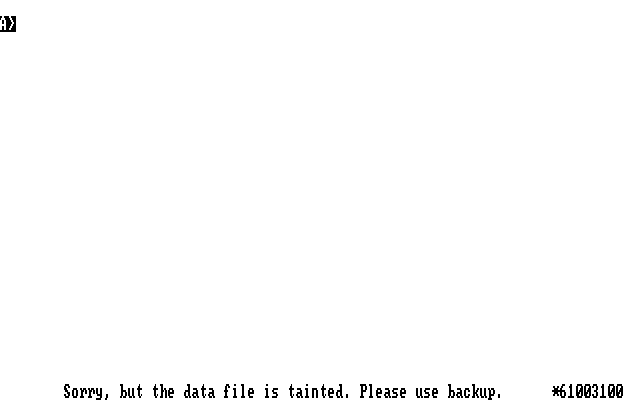

DO-IT Beta 1.2: complains that its data disk is "tainted" and to use a backup, which I do not have. I haven't managed to figure out what's wrong with the data files. You can boot it under CP/M-86 and see the error, at least. The copy of CP/M-86 it has does not seem to be able to boot on an AT, so XT or older. This should support a Mouse Systems mouse but that's sort of irrelevant since it exits immediately on startup.

DO-IT 1.02: I actually have two sets of this dated one week apart, but the earlier one seems incomplete as some of the disks are missing their [Foo].ID files, which might explain why they reissued it a week later. The later copy works, but it's incredibly picky about what it installs on. It needs DOS 2.0-3.2 (it requires VDISK.SYS which is removed in 3.3), requires extended memory despite saying it doesn't, and requires a hard drive but is doing some weird method of drive enumeration where XT-IDEs won't work because it doesn't detect the drive. But if you can get a system that it accepts you can screw around with this thing and be utterly baffled by its UI that feels like it came from a parallel universe where everything seems like it should be familiar but isn't. Arrow keys for cursor control, enter for action ("pick"), +/- switch precision. This should also support a Mouse Systems mouse, but I cannot get that to work.

I also have a copy labeled "RnD Master" that based on dates is also 1.02, or at least a draft version thereof. That three copies of this version survived suggests it was as important to SSC, or at least the developer who kept these disks, as the changes it brought make it seem.

FrontPage 1.0 demo: This weird thing is a disk that you "install" to itself based on what system you have. Out of the box it's flagged bootable but the boot code is all placeholders that it replaces with your own IBMBIO.COM/etc. when you "install" it. Can't say I've ever seen that trick before, but I assume this let them not need to pay for a license to distribute DOS. It does work if you do that and then boot it, though, and it's a decent explanation of the workflow that you'd have using the software. It's honestly pretty neat, IMO.

DO-IT 2.0 demo: Basically the same as the FrontPage demo, except it's before the rebranding and also the installer batch file's help text is just wrong. There's not much reason to run this vs. the FrontPage one except you can see how little they changed with the rebranding.

FrontPage 1.0/DO-IT 2.0: I have half of each of these and no release version of the installer, but amazingly combined with a backup of the PC of the employee who made the installer I actually managed to put together a single complete working build. Except the installer doesn't line up with the disks, because for some reason I cannot comprehend DO-IT 2.0 and FrontPage 1.0 use completely different layouts for their disks, and I have DO-IT files and a FrontPage installer. FrontPage wants a single "master" disk but DO-IT has four of them (named 1A, 1B, 2A, and 2B) and they all contain different content. I cheated and merged them into a single 1.2MB disk. The result does run and you can see the fancy new help system, but as with 1.02 I cannot get the mouse to work under GSX.

FrontPage 1.2: While I only have commercial media for 1.0, and 1.2 was never released, I was able to manufacture my own release of FrontPage 1.2 using the source backups. As this uses GSS*CGI, the mouse actually works in this one. While this is the least authentic release, I recommend this if you want to just try the software out.

Other versions: I've got random disks for printer drivers and such for versions of DO-IT that I don't have a near complete build for, which served mostly to give me dates for releases. Sadly I have no binary versions of DO-IT 2.1 or 2.2. I did discover that one of the disks I have that don't have a label is the otherwise-mythical "Typographer's Utility Disk" (#8) that includes the font editor for DO-IT 1.x. I have no idea what specific version it's for, but based on how this software is architected I suspect it's largely cross-compatible.

DRAW: The copy I have is from March 1985 and versioned 1.1c, though parts of it refer to "2.0" so probably this was an intermediate version that was on its way to becoming 2.0 when this backup was taken. I have nothing else at all before or since to know its version history otherwise. The load/save procedures refer to fonts (with a .dev extension for some reason) and there's some references in the source that state it was meant to draw fonts, but the end user font editor is an entirely different piece of software. I did eventually convince it to run by manually setting up GSX, but I have no idea how to use it. I think it's expecting a mouse (or perhaps a tablet/digitizer) but once again I have no idea how to configure GSX for this. It also somes with a different GSX driver than anything else, probably so it could use a digitizer as input.

GSX and GSS*CGI: As stated, there seems to be very little on the internet about GSX-for-DOS. DO-IT's GSX drivers were written in house, and the source for these (or at least some of them) survived. GSS*CGI is even more obscure. I might now have the most complete set of GSS*CGI DOS drivers in existence, since the entire two other applications I can find that used it only shipped with a handful of drivers that they specifically used but I got a backup of what seems like everything GSS had at the time. Seemingly it was almost solely used otherwise in academic government and industrial applications, none of which have really been archived by anyone anywhere. The drivers were made by GSS as part of the CGI package, so I don't have the source for the drivers themselves. Sadly the driver for the Wyse/Amdek 1280x800 monitors (WY700.SYS) did not survive; it looks like it was provided for 2.1 and I only have a collection of CGI drivers from the failed 2.0 conversion.

The remainder: Mostly internal tools, incomplete backups, and duplicates of other items above. I'm not sure any of this is of particular interest to anyone; things like ASMT86+ are already very well archived. There was a disk labeled "Visicalc data" that I was briefly very excited by but it turned out to just be sample data to use to learn Visicalc. I did find a bunch of personal information that won't be being archived, including one developer's resume (from 1986, possibly they were trying to escape the sinking ship) and another developer's personal budgeting spreadsheet. Also included was an overal budget/investment breakdown from the early days of Creative Freedom Software which is a fascinating document but I'm not sure how to post it sufficiently anonymously.

What of the source code then?

I have the source code for:

- Speed/Art, several versions, none of which are the compiled version I have; in particular none of them have the joystick input code. All are some degree of nonfunctional and most do not even load, and some are missing content files which seem to be a splash screen.

- DRAW, the one version mentioned above.

- Various pieces of beta 1.2.

- Various pieces of some unknown version that is somewhere around 1.01 based on dates.

- The FrontPage installer, in several versions; it looks like there was one for 1.0 (GSS*CGI), one for 1.0 (GSX), and one for 1.1 (GSS*CGI).

- DO-IT 2.0 (August 86 / GSS*CGI), the disks are damaged and I only managed partial reads of some.

- DO-IT 2.0 (September 86 / GSX), almost 100% read with one bad sector on the GSX drivers disk.

- DO-IT 2.1 (October 86), the disks are damaged again and one is completely unreadable.

- DO-IT 2.2 (January 87), likely never even released as the build scripts still refer to "REL21" and also nearly identical to 2.1 based on file modification dates, 100% read.

The source came in a variety of different sub-backups, including the source itself, "objects" (compiled objects and the linking scripts), "drivers", and several libraries used in the larger source like "MTCGI", "STDIOLIB", and "DOITLIB". Not every version had every sub-backup, as for example "drivers" was the source for the GSX driver which was only relevant for the GSX build of 2.0.

The source is all branded DO-IT, except the installer sources I have are all FrontPage. The installer appears to contain all the branding, so my assumption is that there was a DO-IT 2.0 installer somewhere that was not included in the backups I acquired. This is somewhat backed up by the DO-IT 2.x disks and the batch files used to build them in the source archives having a very different layout to the FrontPage disks. I can't speak to why it makes sense to have two different disk layouts for what's almost entirely the same software, but that's SSC for you.

The backups contain .PAS files, .I86 assembly source files, linker command files, the compiler/linker executables, batch files to compile and link it all, and batch files to publish the binary copy to floppies. However, the installer was maintained by an entirely different person, and while I have the source for the installer itself what I do not have any copy of as far as I can tell is the script that creates an install disk. For all I know that was done manually every time. At this point I think I can make one by hand, but that's one thing I'm missing. Nor do I have the source for the demo version. There are files that appear to be test scripts, but I have no idea if these were executed by hand or by script and how to connect them if it's the latter. There are references scattered around to ProKey, a DOS macro system; maybe they used that.

My attempts to read the DO-IT 2.0 (GSS*CGI) source were met with disaster, since I didn't really know how to properly use a GreaseWeazle to do archival for this stuff yet and I wasn't yet experienced with dying floppies. I got most of the contents of most of the disks, but the bits I'm missing I'm pretty sure are now physically damaged and lost as this was how I got to experience what a head crash sounds like. While I feel terrible about that, I was able to get complete reads on the 2.0 (september) and 2.2 sets. 2.1 mostly worked, except the actual source code has disk 3 of 4 in such bad condition I can't get it to read at all even with everything I learned about doing this and that disk may now also be damaged from the attempt. Also, RIP to the TEAC FD-55GFR that gave the life of its lower read head trying to archive the source disks, and the three blank 5.25" disks I was using as test disks to see if I had properly cleaned the heads (as it turns out, usually...). I'm not sure if the drive is just way out of alignment or the head is actually damaged but it won't read a single bit off known good disks now.

Based on the labels of the disks I have and the names in the changelogs, I'm pretty sure I got these disks from the estate of one of the principal developers via somebody that buys estate sale lots and resells them. That developer's name is in the aforementioned investment breakdown, too; if they weren't a founder they were there from the start, at least. I did look to see if I could find an obituary for them, but there were several in just the last year or two with that name. Even with the issues reading some of the source disks, I think this is an incredible find and I am proud to be able to share it with the world.

The source code has been made available, but with the original names redacted. Clearly nobody invovled in this process thought that 40 years later the public would be reading their random source code comments, and I don't want to risk doxxing anyone. If you think you know somebody who worked on this, please let me know--I can confirm against the list of names that I have.

I'm also specifically in search of the missing WY700.SYS GSS*CGI server, or really any additional GSS*CGI display drivers in general. The only software I've seen that might have something is Siemens Simatic APT 1.9, but I've not been able to track that down.

And in general, please reach out to me if you can add anything to this story. I'd love to hear anything that can fill in the gaps or even just provide relevant anecdotes. Even if it's just "my (grand)parent used this", I'd be thrilled to hear anything about what that was like.

Citations

- https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1987-02-10-fi-2182-story.html

- https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1987-04-09-fi-227-story.html

- https://opencorporates.com/companies/us_ca/1245321

- https://opencorporates.com/companies/us_ca/1262246

- https://opencorporates.com/companies/us_ca/0865777

- https://www.computerhistory.org/collections/catalog/102775839

- PC Week, various, in particular issues 1986-07-08 and 1987-03-17